Our examination of overarching trends revealed:

- An increase in malware incorporating hidden virtual network computing (HVNC), keylogging and remote control functionalities.

- A growth in offers by nontechnical cybercriminals fueled by the availability of leaked source code online.

- Malware loaders bypassing Android 13+ accessibility restrictions.

- A malware developer’s good reputation is often more important than technical features due to the competitiveness of offerings.

- Threat actors' successful exploration of near-field communication (NFC) relay techniques.

- Threat actors repurpose leaked malware code, adding capabilities or simply rebadging it as a new offering.

Android malware continued its rapid expansion in 2024. Threat actors discovered innovative methods to distribute new campaigns, refined existing products and introduced new families into the underground market. As part of our ongoing surveillance, we closely monitor both prominent forums and public repositories to identify emerging strains, assess their capabilities and enhance our extraction and — where feasible — emulation support. This report aggregates our key findings from 2024, including notable campaigns, updates and releases. We then examine overarching trends, such as the increase in malware incorporating HVNC, keylogging and remote control functionalities; a growth in offers by nontechnical cybercriminals fueled by the availability of leaked source code online; and threat actors' exploration of the NFC relay technique. Finally, we provide a comprehensive overview of the collected Android products and services and examine the most prevalent features, types of offers and prevailing price ranges.

This detailed analysis comes from Intel 471’s Malware Intelligence, which provides ongoing collection and analysis of mobile and desktop malware families to help defenders write detection rules. Malware Intelligence also delivers technical data that can be drawn on to conduct threat hunts using our HUNTER threat hunting platform, which contains prewritten hunt queries for a variety of security incident and event management (SIEM), endpoint, detection and response (EDR) and logging aggregation platforms. Register for the Community Edition of HUNTER, which contains free threat hunt query content, here. For more information, contact Intel 471.

Increase in hidden virtual network computing, keylogging, remote control capabilities, decrease in web-injects

Over the past year, the Android malware landscape has experienced a significant surge in threats incorporating HVNC, keylogging and remote control capabilities — thereby keeping on-device fraud alive in the mobile space, even as similar activities decline in the desktop malware arena. This shift away from traditional web-injects, which require frequent updates and third-party resources, toward stealthier keyloggers reduces both the complexity and cost of maintaining large-scale fraud campaigns. While web-injects remain at moderate levels, keyloggers that exploit Android’s accessibility services have become increasingly popular for harvesting sensitive data. Once this information is collected, malware operators often deploy HVNC to reconstruct the infected device’s screen on the server side, providing a real-time view of the victim’s activity. When attackers move to execute illicit actions, they simply present an overlay to the user, concealing the unauthorized tapping, swiping or text entry taking place behind the scenes.

While we previously expected a broader adoption of automated transfer systems (ATSs) for banking apps, their implementation likely proved to be labor-intensive for developers. Consequently, threat actors have favored manual, on-device fraud executed through remote screen control and abuse of accessibility features — an approach that requires significantly less overhead and yields high success rates. These emerging methods demonstrate how Android malware authors continually are refining their techniques, reducing operational friction for themselves while significantly increasing the threat to financial institutions and end users alike.

Malware loaders circumvent Android 13 accessibility restrictions

In May 2022, Google implemented a security enhancement aimed to curb the abuse of accessibility services by malicious applications. This measure blocked accessibility access for sideloaded applications, significantly reducing the spread of malware that exploited this sensitive feature. However, threat actors adapted by employing session-based package installers, thereby circumventing Google’s new safeguard and facilitating the deployment of malicious payloads. One notable example of such an installer is TiramisuDropper, which has gained widespread popularity among operators of Android banking trojans such as Hook, TgToxic and TrickMo.

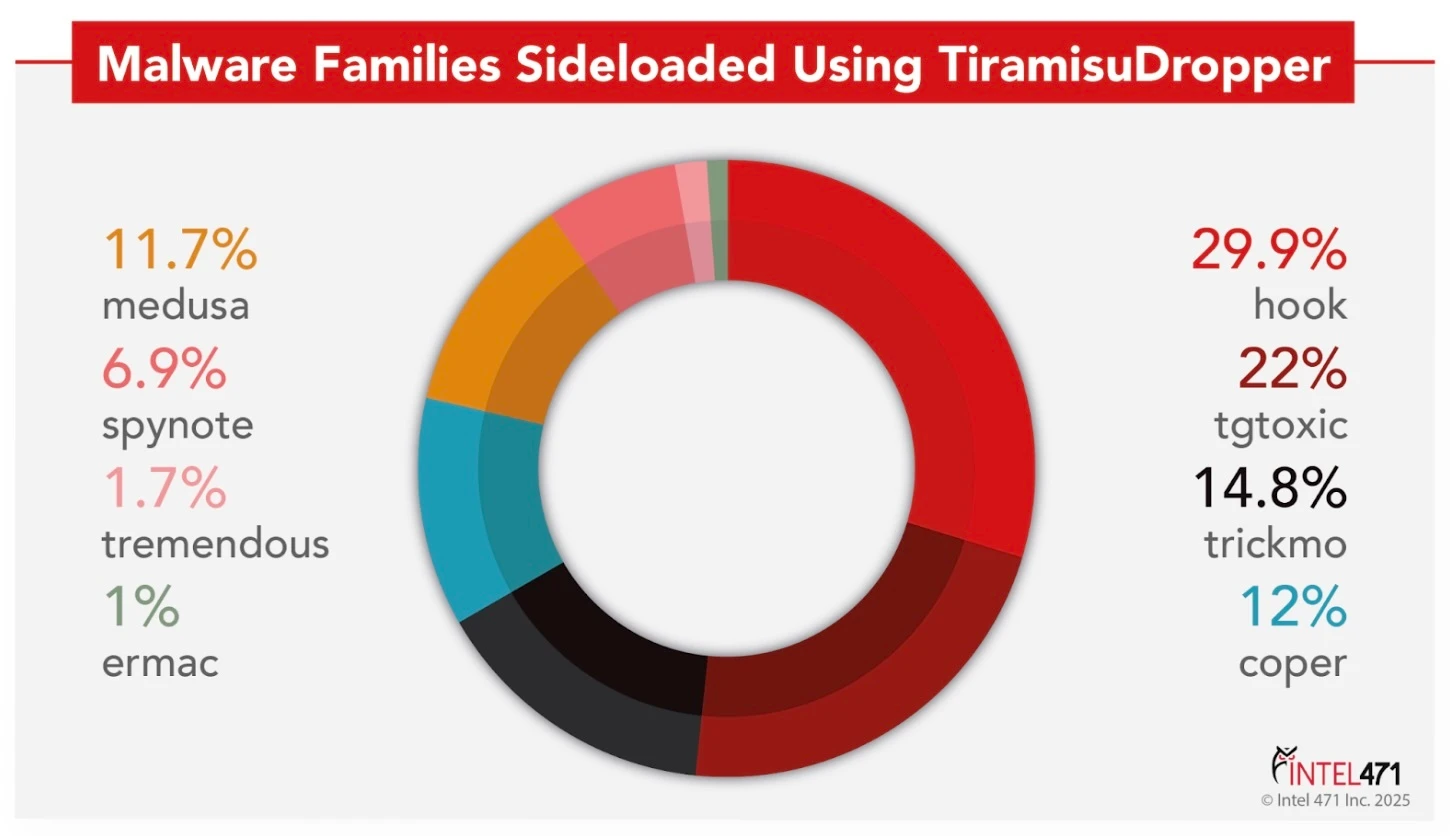

The graph depicts malware families sideloaded leveraging TiramisuDropper from April 4, 2024, to Dec. 31, 2024.

In April 2024, the actor Samedit_Marais aka BaronSamedit shared the Brokewell Android loader on the Exploit cybercrime forum. The loader allegedly can bypass accessibility restrictions implemented in Android 13 and later versions. By making the source code publicly available, the actor enabled other malware developers to integrate this loader component into their own solutions. Consequently, it is highly likely we will see an increase in malware variants designed to evade accessibility defenses. Additionally, as suggested by the ThreatFabric threat research company, it is probable that existing "dropper-as-a-service" providers such as TiramisuDropper, which currently offer this capability as a unique feature, either will cease their services or undergo significant restructuring.

Leaked Android source code spurs rise in nontechnical cybercriminals

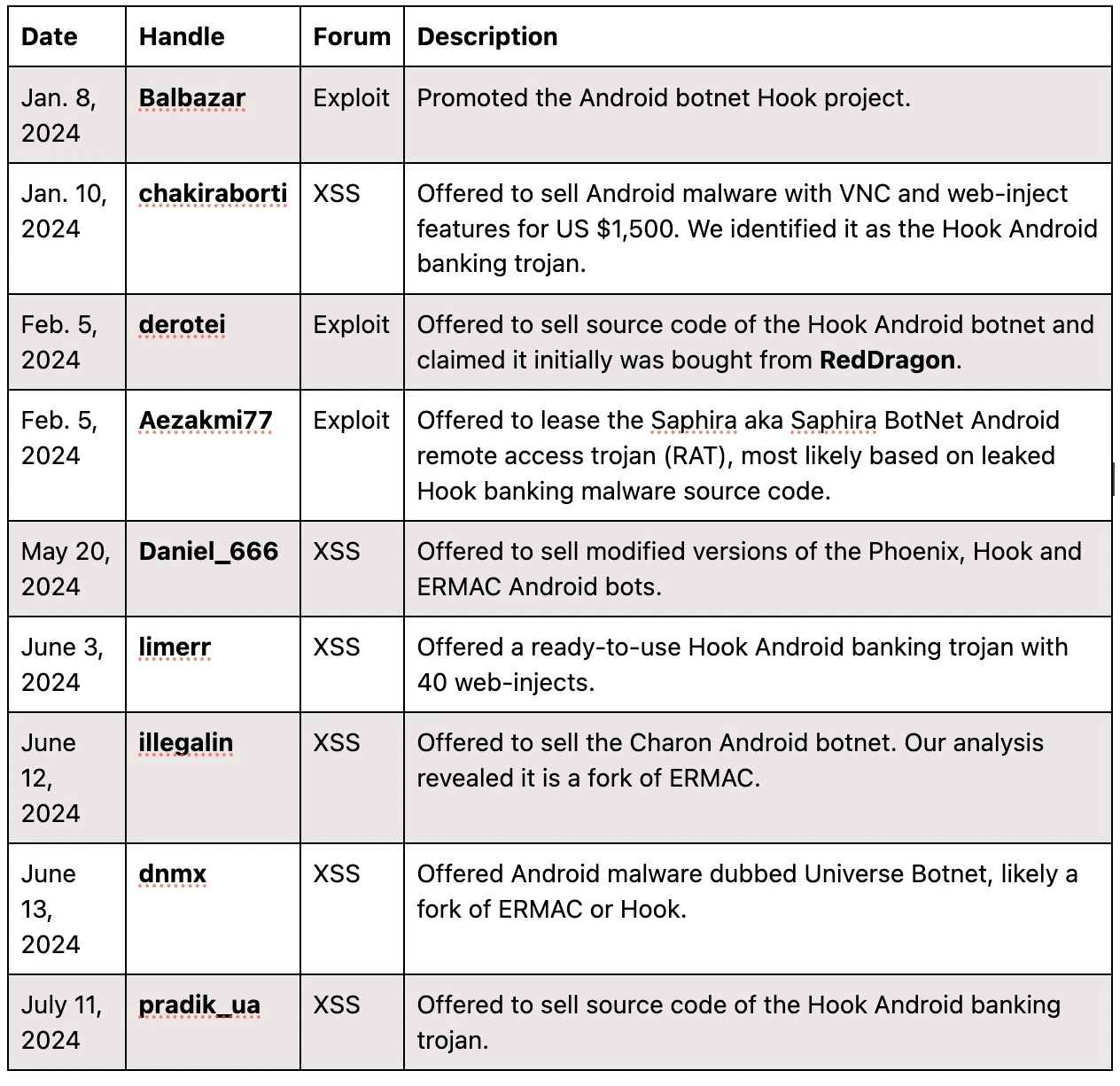

On July 24, 2023, Intel 471 discovered the GitHub platform user 0xperator released what is believed to be source code of the Hook Android banking trojan. The posted files included source code of the Hook builder panel version 2.0.12. Subsequently, on Aug. 21, 2023, the actor RedDragon aka Pasker confirmed the source code of Hook was leaked. In 2024, we observed at least nine malware offers that were based on either Hook or ERMAC source codes.

In July 2024, we pivoted on the resources present in the original Hook panel and identified at least 16 additional panels allegedly customized by threat actors including:

- AZAZEL

- DarkBan

- EVERSPY 3.0

- FIREBOT

- FIXER WORLD

- LOOT

- Mystry Man

- NOTHING

- Pegasus

- SAMBOT

- Saphira

- Scarab

- THANOS

- Universe

- ZeuS

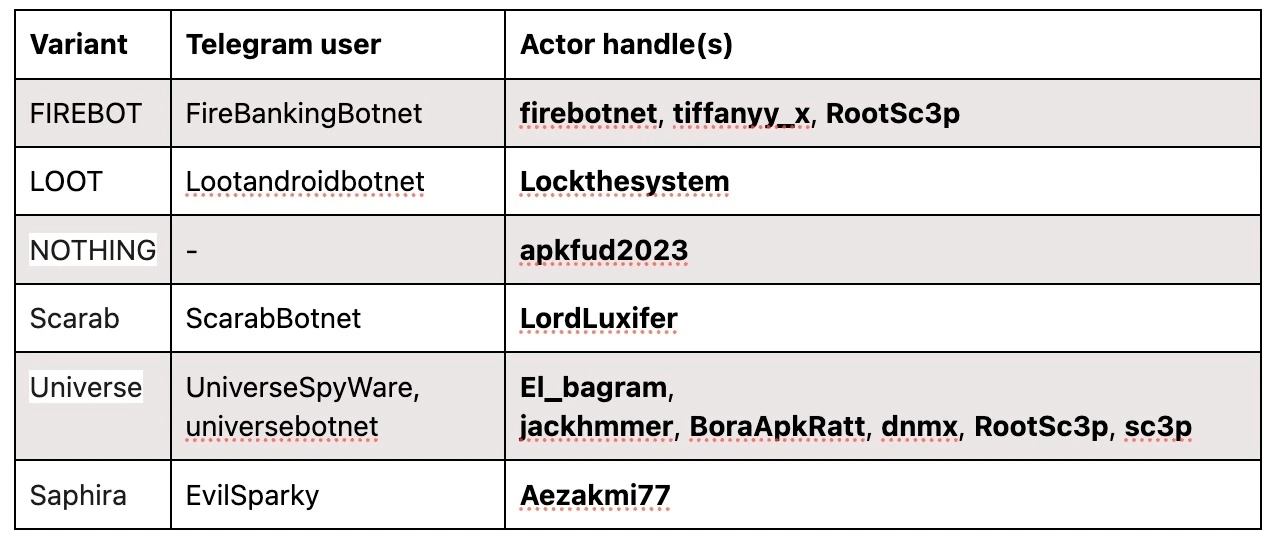

The table below lists the observed variants along with their associated adversary attributions based on data gathered from control panels and posts on underground forums.

The actor RootSc3p is identified as being behind both the FIREBOT and Universe variants. Given that there was no mention of the FIREBOT variant on underground forums, it is plausible the actor or actors experimented with different names before officially listing the Universe Botnet for sale in June 2024.

As demonstrated by the offers listed above, recent leaks of advanced Android malware source code — particularly Hook and ERMAC — have drastically lowered the barrier to entry for cybercriminals lacking significant technical expertise. Historically, these sophisticated tools were developed by highly skilled threat actors and monetized through malware-as-a-service (MaaS) models. However, once the source code became publicly accessible, even less-experienced operators began repackaging and reselling it as “new” or “unique” products — often without gaining much traction among established threat actors. This trend has triggered an uptick in underground scams, with would-be sellers promoting recycled or nonfunctional malware with the hope of profiting from unsuspecting buyers.

In August 2024, ESET researchers disclosed a new malware strain called NGate that targeted clients of three major banks in the Czech Republic. NGate abuses NFCGate, an open source tool originally meant for legitimate security testing of NFC signals. NFC is short-range wireless technology that allows devices to communicate when they are very close together, such as by tapping a credit card or phone with a digital wallet on a payment terminal. By misusing NFCGate, attackers can transmit NFC information from a victim’s infected phone to another device under their control, enabling them to clone the card and make unauthorized payments or withdraw cash from ATMs.

While the campaign described by ESET involves multiple instances of phishing and social engineering, the ultimate objective remains unchanged — deceive victims into installing an application that harbors NGate malware. Steps actors related to the malware leveraged include:

- Initial access. The victim receives a deceptive short message service (SMS) message claiming to address a potential tax refund or other urgent matter. The message directs them to a short-lived domain disguised as a legitimate banking website or an official mobile banking app. When the victim installs the app from this domain, they unknowingly infect their Android device with NGate.

- Phishing for sensitive data. After installation, NGate presents a fake banking interface that prompts users to enter personal details such as their banking client ID, date of birth and personal identification number (PIN). These credentials are sent to the attacker’s remote server.

- NFC enablement. NGate urges victims to enable NFC on their phones and tap or place their physical credit card against the back of the infected device.

- NFC data capture and relay. Using NFCGate, NGate captures the card’s contactless payment information in real time and relays it through a server to the attacker’s Android phone. This allows the attacker’s device to act as a clone of the original card by leveraging host card emulation (HCE).

- Card emulation and fraud. Armed with the cloned card data, attackers can make unauthorized withdrawals at NFC-enabled ATMs or execute illicit purchases through services such as Google Pay. If the ATM withdrawal method fails, they may transfer funds from the victim’s accounts into other accounts under their control.

In November 2024, ThreatFabric researchers uncovered another campaign where cybercriminals exploited NFCGate to execute large-scale fraud with minimal risk. In this scenario, the attacker — a cybercriminal possessing stolen card credentials linked to a mobile payment system — uses NFCGate on their phone to relay transaction data to a mule device. The mule, also equipped with NFCGate, physically completes purchases at point-of-sale (PoS) terminals in retail stores. This method allows cybercriminals, who can link cards to mobile payment services, to anonymously purchase goods in stores while scaling the fraud by potentially using multiple mules in various locations to carry out transactions.

Shortly after NGate’s discovery, we observed an uptick in online discussions and advertisements for NFC relay tools on underground forums. For example, the actor Scanner expressed interest in software capable of relaying NFC data for money withdrawals, while the actor KarakeJo aka Karake, odahodah, Odah Al-Suhaimat, Odah Suhaimat, ОДА СУХИМАТЬ offered an Android-based contactless payment data relay tool. These developments highlight a worrisome trend in financial cybercrime as more actors recognize the potential of NFC relay techniques for fraudulent activities and cashout schemes.

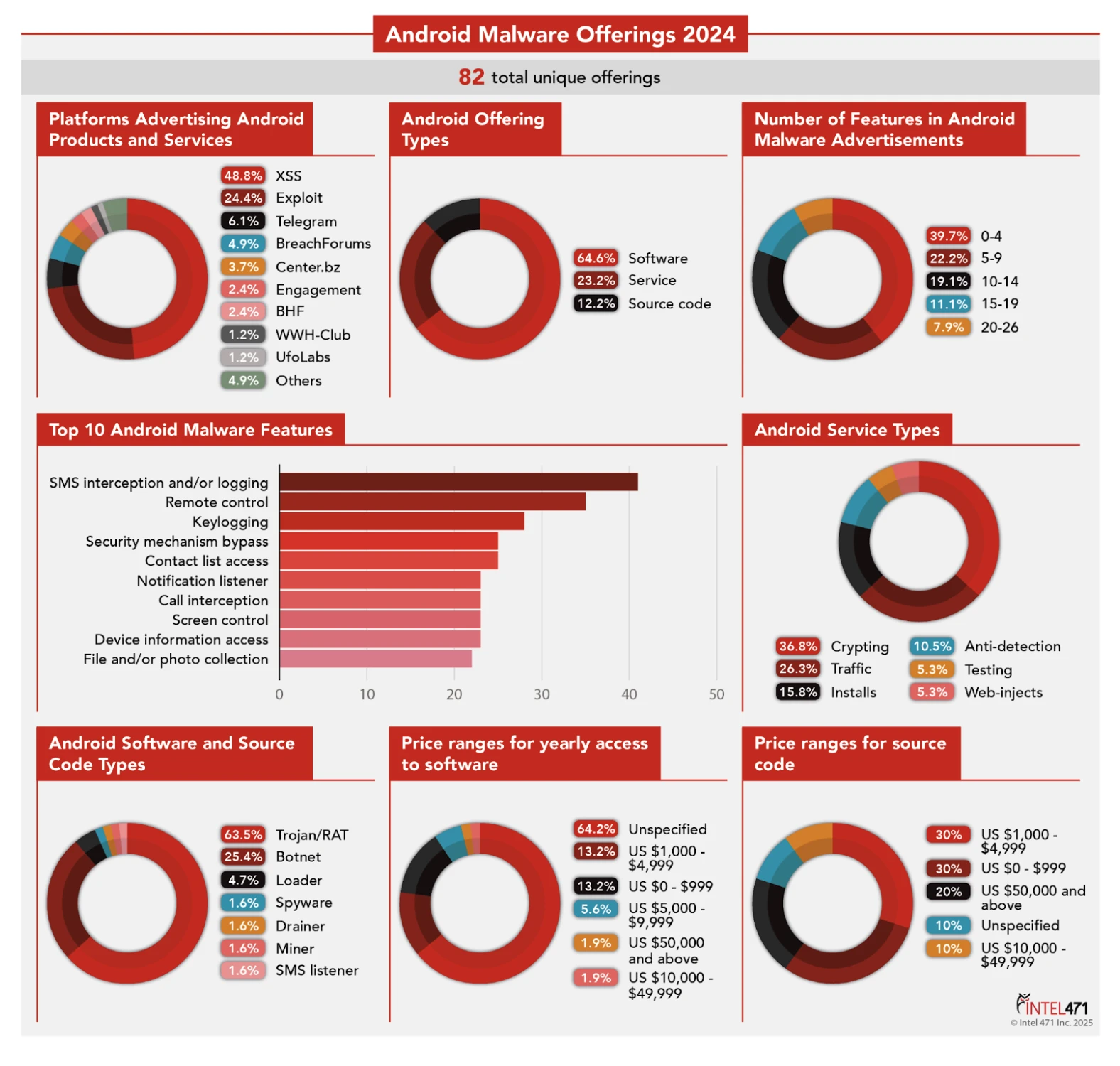

In 2024, we identified and examined 82 distinct Android malware offers. Of these, 64.6% pertained to malicious software, 23.2% pertained to services and 12.2% involved the sale of source code. The most prominent platforms for advertising these offers were the XSS and Exploit cybercrime forums. Analysis of the Android software and source code types revealed 63.5% involved trojans or RATs, 25.4% focused on botnets and the remaining 11.1% comprised other malicious tools. The price for software was not specified in most instances. For source code, 30% of the listings sought US $1,000 to US $4,999, 30% sought under US $1,000 and a small number sought US $50,000 or more. With respect to services, crypting services dominated the market at 36.8% of all listings, followed by traffic services at 26.3% and install services at 15.8%.

The image depicts statistical data about Android malware offers in 2024.

Additionally, we conducted a comprehensive review of each Android software offer and aligned its capabilities with a catalog of 32 potential Android malware features. The analysis revealed SMS interception and/or logging, remote control and keylogging functionalities were among the most frequently advertised features. Notably, 39.7% of sellers listed zero to four features, 22.2% listed five to nine and 19.1% listed 10 to 14.

Of the 53 software offers analyzed, only a select few demonstrate the potential to succeed in this highly competitive marketplace. A key differentiator is the seller’s reputation, which often carries more weight than technical innovation alone. Given the prevalence of established, reputable vendors in the market, newcomers must offer distinctive features and deliver significant value beyond what already is available. Factors such as robust customer support, regular updates and competitive pricing are crucial for differentiating these offers and building confidence among buyers.

Looking ahead, several notable trends are set to reshape the Android malware landscape. One is the ongoing shift from web-injects to stealthier keylogging techniques, a transition that minimizes operational overhead while enhancing campaign flexibility. Despite previous expectations, the widespread adoption of ATSs has not materialized. Instead, many attackers continue to prefer manual, on-device fraud executed through remote screen control and accessibility abuse, which offers simpler execution and higher returns on investment. Additionally, we anticipate a growing emphasis on integrating loader components capable of bypassing Android 13+ security measures into Android malware, a trend that could potentially lead to diminished interest in "dropper-as-a-service" offers. Finally, the growing interest in NFC relay techniques for fraudulent transactions and cashout indicates an escalating risk of large-scale financial scams in the near future.

Given the dynamic nature of this threat environment, rigorous threat monitoring, regular vulnerability assessments and continuous intelligence sharing are essential to identify and address evolving threats before they can gain traction.