After compromising a system, attackers often seek ways to maintain persistence. This involves setting up mechanisms that ensure either their malware or access is maintained even if defenders close off other access avenues. One example is adding a program to a startup folder or referencing it with a registry run key so that piece of malware runs again every time a system is restarted. Another example is creating more accounts within an organization’s remote access software to ensure that if a suspicious account is turned off, others will be available as back ups. In this threat hunting case study, we cover a persistence technique used by a variety of ransomware groups, including DragonForce — a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) group that has been in the public eye the last few months.

The DragonForce group launched in 2023 and initially gained attention with politically motivated attacks, targeting entities that aligned with its ideological beliefs. Over time, the group pivoted to financially motivated extortion campaigns. In 2025, Intel 471 has tracked 53 possible victims of DragonForce. The group has stated it has a “cartel” operation model whereby interested actors may create their own “brand” and launch attacks using DragonForce’s infrastructure, tools and resources, such as its data leak site. This concept is barely different from RaaS, but the idea is that the affiliates may adopt their own name rather than use the DragonForce name.

The group’s attacks have been seen globally, particularly affecting high-profile targets in the retail, financial and manufacturing sectors across North America, Europe and Asia. Its affiliates employ a dual-extortion strategy where after encrypting data, they threaten to release exfiltrated information if the ransom is not paid. The group doesn’t have its own encryptor. Instead, it has leveraged leaked ransomware builders from other ransomware groups including LockBit and Conti. It is unknown where DragonForce is based, although its main operator has written posts in Russian on the RAMP cybercrime forum, which stands for Russian Anonymous Market Place. There have been suggestions that it might be based in Malaysia, as there is a hacktivist group called DragonForce Malaysia, but that group denied any association with the DragonForce RaaS in early 2024.

The DragonForce group has been referenced related to data breaches in the U.K. affecting the retailers Marks & Spencer and Co-op. The breaches caused severe disruptions at both organizations and with M&S involved encrypting ransomware. A group of native English-speaking attackers claimed responsibility to the BBC, and it is suspected they may be affiliates of DragonForce. The prevailing thought is that these threat actors may be part of TheCom online ecosystem. TheCom is a large dispersed group operating on forums, Telegram and Discord that specializes in cryptocurrency theft, data breaches and phishing. The group is also referred to broadly as Scattered Spider, as it uses the same tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs), although Com is a more encompassing term. Com threat actors are relentless and persistent, often calling organizations and impersonating help desk staff in attempts to get passwords and multifactor authentication (MFA) tokens reset for privileged accounts.

Threat hunting focuses on detecting adversary behaviors that are derived from incident response investigations. This intelligence-lead approach allows us to focus on the TTPs that adversaries repeatedly use in attacks and that threat actors are less likely to change. TTPs are at the very top of the Pyramid of Pain, which is the conceptual model charting detectable artifacts related to attacks and how difficult they are for adversaries to change.

This is a more effective approach to threat hunting than using indicators of compromise (IoCs), which are frequently changed. Adversaries can and do easily change malware with crypters to create new hash signatures as well as switch command-and-control (C2) servers and IP addresses used as part of attack infrastructure. Still, we’d be remiss not to do a scan for known IoCs as part of an investigation, and it may represent an easy instant confirmation of a compromise. For example, an IoC related to a persistence technique could be the modification of a registry key to the name SOCKS along with an executable named 69d30d7.exe, an odd-looking name that should raise suspicions. We should do an IoC scan for both of those names, and it could result in a quick win, potentially reducing the investigation time by hours, days or even weeks. Not finding those terms, however, does not mean that the environment has not been compromised. This is where behavioral threat hunting can fill in the gaps.

A common method adversaries and malicious software alike use to achieve persistence is adding a program to the startup folder or referencing it with a registry run key. Adding an entry to the run keys allows the referenced program to be executed when a user logs in. For attackers, this ensures this malware runs without the user needing to execute it or the user to be phished again, allowing persistent access. The technique is used by a wide variety of actors aside from DragonForce, including APT15, APT27, APT31, APT38, CL0P, Charming Kitten, DarkCasino, Diamond Sleet, FIN6, FIN7, Labyrinth Chollima, Lazarus, Mad Liberator, Mustang Panda, TheCom, TA577, TAG-67, UNC2465, Water Gamayun and Water Hydra.

Will endpoint security software catch this type of modification at the time when it occurs? Possibly. Endpoint, detection and response (EDR) security software applications are often configured to audit registry run keys because adversaries frequently use this technique. For organizations that do not run EDR, it could be potentially tricker. Pre-ransomware activity often comprises discovery, persistence and then defense evasion, which can take multiple forms. After gaining persistence, attackers may use a defense evasion technique such as excluding their executable from Windows Defender. Or they might try to completely turn off Defender, which can be done using the Set-MpPreference in PowerShell.

We can threat hunt for suspicious registry run keys. Intel 471’s HUNTER platform contains a specific threat hunt package called Autorun or ASEP Registry Key Modification (ASEP stands for auto start entry point). The threat hunt package contains prewritten queries for EDRs and logging platforms including CarbonBlack Cloud - Investigate, CarbonBlack Cloud - LiveQuery, CarbonBlack Response, CrowdStrike, CrowdStrike LogScale, Elastic, Google SecOps, Microsoft Defender, Microsoft Sentinel, Palo Alto Cortex XDR, QRadar Query, SentinelOne, SentinelOne Singularity, Splunk, Tanium, Tanium Signal and Trend Micro Vision One.

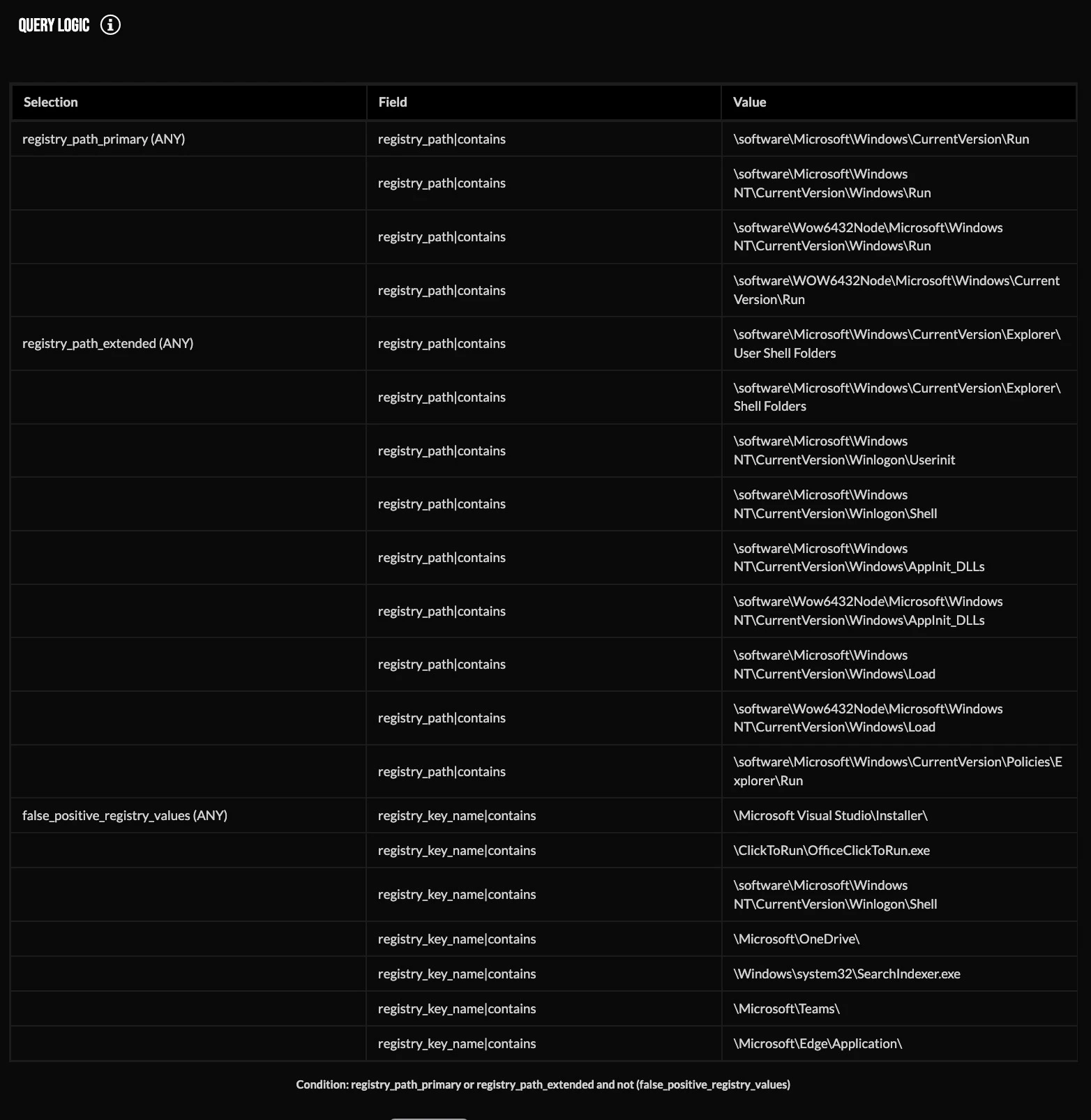

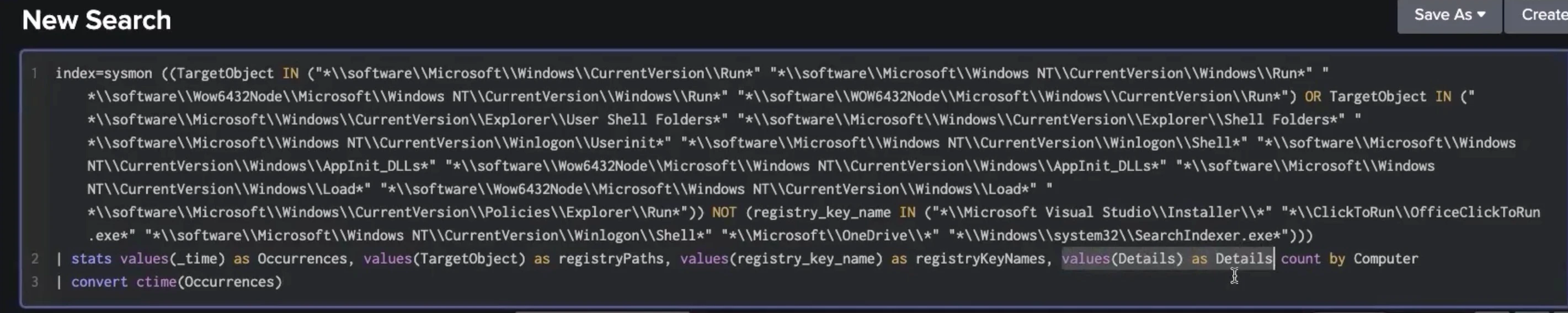

To detect this technique, what values should be hunted for? The following screenshot shows the query logic:

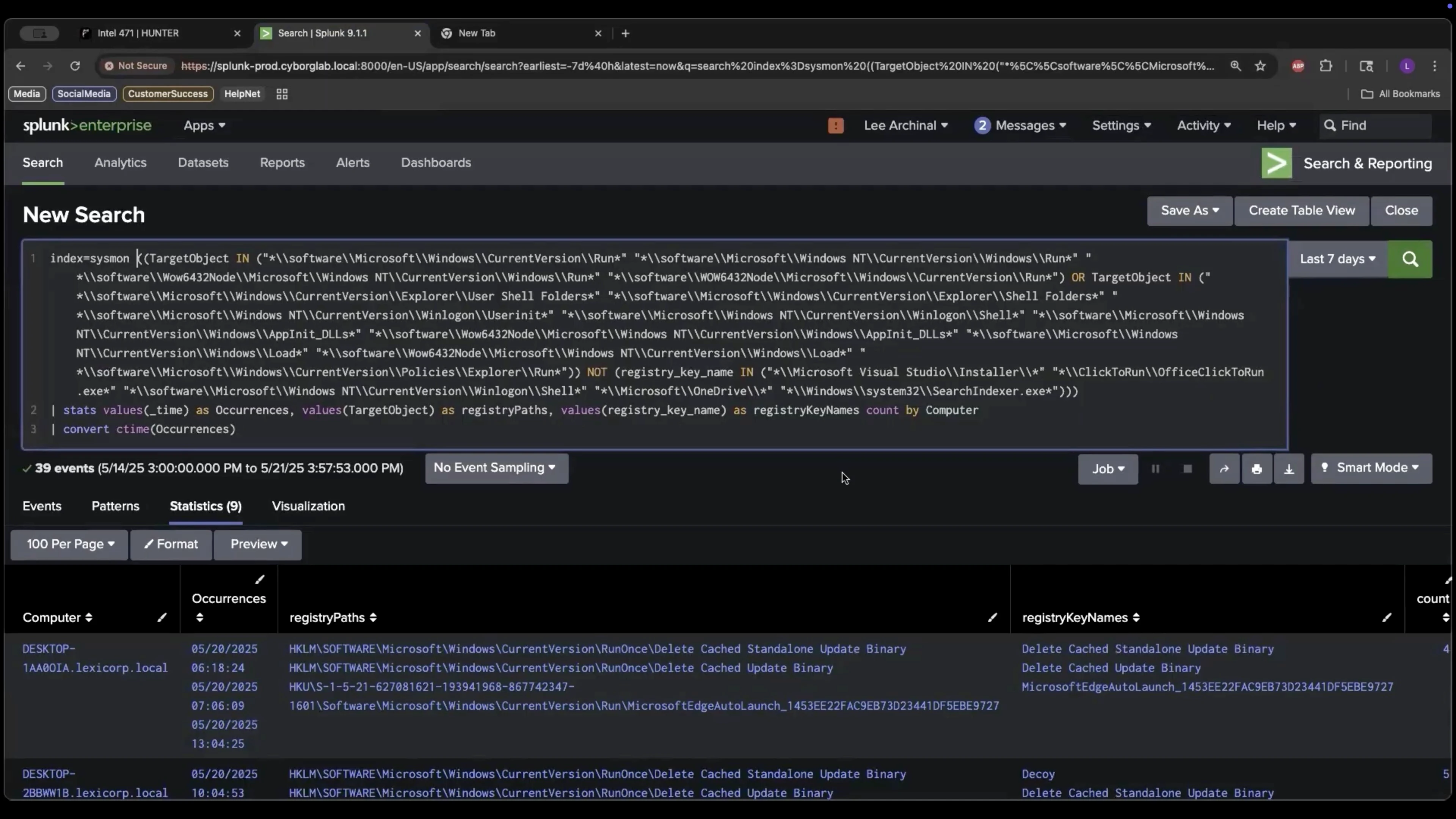

There are several registry key paths that have the power to execute an application upon logon, which are included in the query logic above. The reason we are looking at registry key paths rather than registry key values is because adversaries can choose any name for their malware. It’s better to look at the registry key path to see if anything has changed and then determine whether it is suspicious. False positives are possible, of course, but weeding those out is part of the threat hunter’s job. Below are the results for running the query using Windows Event Logs ingested into Splunk.

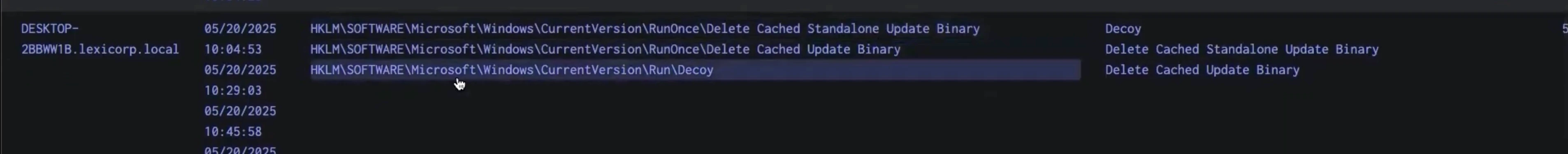

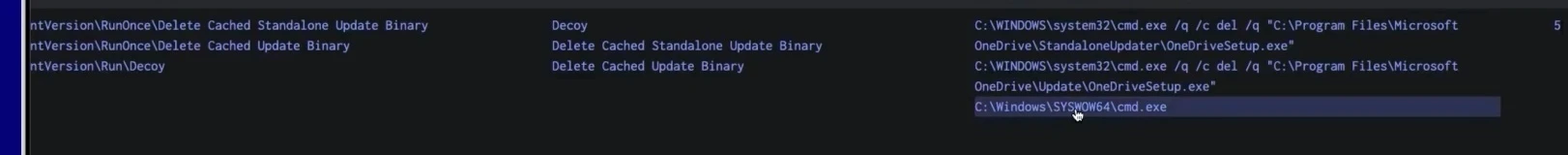

There are quite a few results. The first two are “Delete Cache Standalone Update Binary” and “Delete Cache Update Binary.” Scrolling further down, this appears to be on all of our machines, which may be an indication that this may be a legitimate behavior if it can be connected with a legitimate use case. If so, this result can be excluded. But there’s another result with a registry key that is suspicious — “Decoy.”

Decoy was created for purposes of this threat hunt as an example, but it gives us an idea of what to investigate. Now that we know what to drill down into, we can modify the original query to look for the executable or script or commands that correlate with this registry key by adding a “Details” parameter to the query logic. This will show specifically what this registry key is linked with on this computer whose name is DESKTOP-2BBWW1B.lexicorp.local. The next screenshot shows the Details parameter in the lower right-hand corner.

The results return:

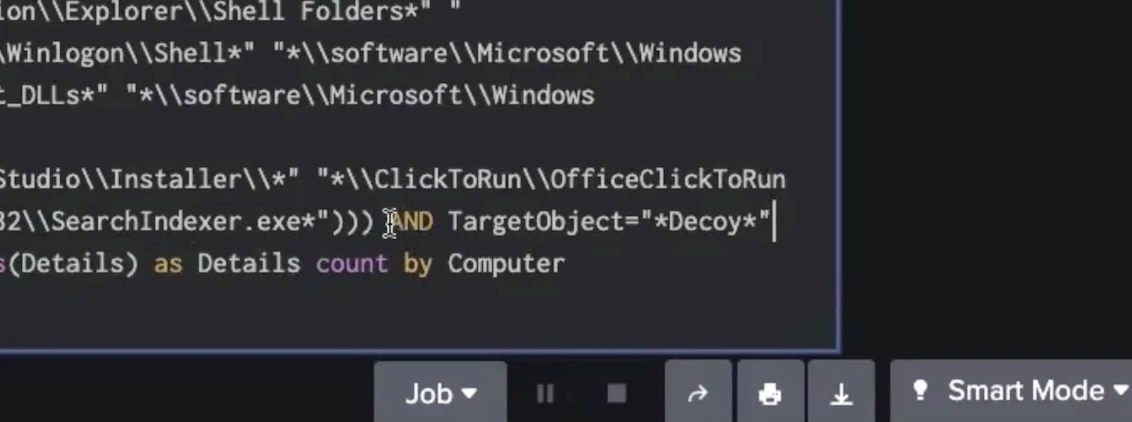

There’s a suspicious file linked with the decoy registry key: the 32-bit version of the command interpreter executable running on a 64-bit machine. We can take another step in the investigation and add another search term in the query to call out the Decoy registry key name specifically:

By adding the Decoy parameter as seen above, it’s possible to isolate the Decoy registry key name and confirm that the particular desktop that appeared earlier in the broader search results is indeed the compromised machine.

This concludes this threat hunting tutorial for a common technique used by attackers. A video version is available here. The Community Edition of HUNTER contains this free threat hunt, which is available upon registration. The Community Edition also contains other free hunt packages and visibility into HUNTER’s subscription-only library of advanced threat hunting packages, detailed analyst notes and proactive recommendations. Happy hunting!